How do artists depict art? It’s a fascinating question, and in today’s post I’d like to consider a few examples of paintings within paintings in American Stories. How are the figures depicted in relation to works of art, and how do the depicted works themselves function within the overall narratives? There are many examples in the exhibition’s more than one hundred iconic paintings, but let’s start with depictions of art in museums:

|

|

|

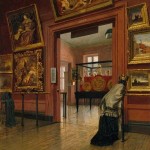

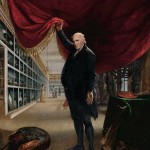

Above, from left to right: Frank Waller (American, 1842–1923). Interior View of The Metropolitan Museum of Art when in Fourteenth Street (detail), 1881. Oil on canvas; 24 x 20 in. (61 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1895 (95.29). Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Samuel F. B. Morse (American, 1791–1872). Gallery of the Louvre (detail), 1831–33. Oil on canvas; 73 3/4 in. x 9 ft. (187.3 x 274.3 cm). Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Daniel J. Terra Collection (1992.51). Photograph: Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Resource, NY; Charles Willson Peale (American, 1741–1827). The Artist in His Museum (detail), 1822. Oil on canvas; 8 ft. 7 3/4 in. x 79 7/8 in. (263.5 x 202.9 cm). Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison Jr. Collection) (1878.1.2).

Museums can play a number of roles, but missions of education have been common throughout history. In some cases, these didactic missions are evident in works of art as well. Frank Waller’s painting shows two of the second-floor galleries of the Met (when it was located on West Fourteenth Street), and it includes works that were actually on view at the time. The painting above the lintel at the center is The Wages of War by the American artist Henry Peters Gray, but most of the other works that have been identified are by European masters. To the left of the door, for instance, are Anthony Van Dyck’s painting of Saint Rosalie and, above it, Cornelis de Vos’s Portrait of a Young Woman. We know from his writings that Waller admired European art; perhaps by directing viewers toward these works he hoped to instruct their tastes as well. He may even have wanted his fellow Americans to follow the example of the studious female visitor he depicts, who leans in intently to absorb art’s lessons.

Samuel F. B. Morse’s painting of the Louvre’s Salon Carré also features European masterworks. Less concerned than Waller with accurately depicting the gallery space, Morse was perhaps more ambitious in presenting lessons to a broader audience. The American figures depicted—including James Fenimore Cooper, and Morse himself—are shown studying and copying the masterworks. Waller exhibited this monumental canvas in New York and New Haven as both a spectacle and a tool for teaching European art, and even produced a pamphlet identifying all of the featured works to assist in educating his audience.

In Charles Willson Peale’s painting, the artist depicts himself lifting a theatrical red curtain to reveal the interior of the Philadelphia Museum, which he and his family founded and managed. The galleries were devoted to the natural sciences and art, with fossils and portraits occupying the same spaces. Through the strategic arrangement of objects intended to instruct visitors to his museum—and viewers of his painting—Peale established a hierarchy of life forms: human beings, represented in portraits, surmount dioramas of bird specimens, which in turn stand above the fossils of extinct animals resting on the floor in the foreground. Like the Louvre and the Met, Peale’s museum was a place of learning, but it was also devoted to creating spectacles. The artist shows himself lifting the curtain just enough to provide a partial, tantalizing glimpse at the mastodon skeleton in the background at right.

It’s also interesting to note how Peale depicts the reactions of the male and female visitors in this painting. While the adult man and his young companion respond calmly—the boy even holds a book, emphasizing his rational and intellectual nature—the woman throws her hands up in surprise, overcome with emotion at the wonders she sees. So we see that Peale has encoded lessons of another sort—i.e., “the nature of the sexes”—in this painting as well. (Similar gender differences are apparent in another work in the exhibition: Francis William Edmonds’s The Image Pedlar, in which a door-to-door vendor proffers small sculptures of fruit to women, while men admire busts of great historical figures.)

Far from the educational, instructive narratives mentioned above, several paintings in the exhibition communicate more commercial or even self-serving messages, as in the two works shown here:

Above, from left to right: Matthew Pratt (American, 1734–1805). The American School, 1765. Oil on canvas; 36 x 50 1/4 in. (91.4 x 127.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Samuel P. Avery, 1897 (97.29.3). Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art; William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916). The Tenth Street Studio, 1880. Oil on canvas; 40 3/8 x 52 1/2 in. (102.6 x 133.4 cm). Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Albert Blair (48:1933).

Matthew Pratt’s painting tells a story—or perhaps a tall tale—about his training in Benjamin West’s London studio. West is featured on the left, assisting a group of American artists who draw at a table, while Pratt, at right, suggests his more advanced status by depicting himself as a painter working independently on a canvas. In actuality, Pratt had no formal training before he arrived in London in 1764, but by depicting himself with a canvas, he boldly advertises his professional-level skills to potential patrons. William Merritt Chase’s work, like Pratt’s, contains a self-portrait. The artist presents himself seated in the shadows at right, conversing with a friend, model, or patron. Chase was an avid collector with eccentric tastes, and his studio is shown overflowing with paintings, prints, lamps, rugs, and tapestries, presumably brought back from his travels. While he often used these items as props in his work, they also announced his sophisticated and worldly tastes and increased his appeal to elite clients.

Finally, consider Thomas Le Clear’s view of a photographer’s studio, seen below:

Thomas Le Clear (American, 1818–1882). Interior with Portraits, ca. 1865. Oil on canvas; 25 7/8 x 40 1/2 in. (65.7 x 102.9 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by the Pauline Edwards Bequest (1993.6).

While the scene may look mundane, it is actually a complete flight of fancy. The figures posing for a photograph are Parnell and James Sidwell, a sister and brother who died as adults before the painting was commissioned by their surviving brother, but who are here represented as children. As Margaret Conrads pointed out in the essay she contributed to the American Stories catalogue, the painting challenges the idea that photography is more truthful than painting. Just as the painter fabricates the scene, so does the photographer at right use a backdrop to fabricate the appearance of nature. The inclusion of “Old Master” canvases and plaster casts of classical sculptures like the Venus de Milo in the painting further emphasizes the way in which images may depend on other images to come into being. What is real and what is fabricated, here, after all? While the photographer may rely on a painted backdrop, painters also rely on certain prototypes in their work.

These are just a few examples from American Stories of paintings that incorporate or reference other works of art. I hope you enjoy looking for more on your own.

—Katie Steiner